Mapping out a plan for restoring the correct Winne name across America

For whatever reason, the Winne name has been changed many times over the years, mainly beginning in the mid to late eighteen-hundreds. This is not a good thing. The only organization this type of thing benefits is the state governments that allowed this to happen, and for now, we don’t know exactly why it did.

We are on a mission to restore the Winne name back from some of the common misspellings that exist out there like: Winnie, Winney, Wynne and Winn. Below we will map out the plan for restoring the various markers or signs that exist that need to be restored to the correct name.

- Vloman’s Kill in New York changed to Winne Creek

- Winne Street restored in New York City

- Winnie, Texas changed to Winne, Texas

- Restoring correct street names across America that are proven to be tied to the Winne family

- Restoring Winne’s Dock or building a monument, along the Hudson River in New York

- Restoring Winne land in Mount Tremper, New York, with a monument and potentially a museum

You can follow #WinneRestored here and across social media for more updates.

Peter Winne and the Mohawk River

On August 18, 1741, Peter Winne was officially granted ownership of a series of small islands in the Mohawk River near Little Falls, a historically strategic location in upstate New York. This land grant marked a continuation of the Winne family’s pattern of settling and investing in riverfront property to support trade, agriculture, and early development in colonial America.

The grant awarded Peter Winne “all the small islands in the river, from the upper end of the Great Falls (now called Little Falls) to the place where Canada Kill falls into said river.” These islands were situated between two major tributaries of the Mohawk River and were valued not only for their fertile land but also for their proximity to trade routes that preceded railroads and highways. This grant came six years after nearby islands on the opposite side of the river were awarded to German settlers through the Petrie and Palatine patents of 1725, reflecting growing colonial interest in the region’s economic potential.

Winne’s acquisition of these islands wasn’t incidental—it was part of a larger legacy. The Winne family had deep roots in New York, with ancestors originally from Flanders (Belgium) who settled in the mid and upper Hudson River Valley during the Dutch colonial era. Prior generations of the Winne family had already established landholdings on islands south of Fort Orange (now Albany), building a reputation as early entrepreneurs who relied on river transport to fuel commerce, agriculture, and milling.

Like the family’s better-known ventures along the Hudson River—including Barent Winne’s bustling dock near Cedar Hill—Peter Winne’s Mohawk River holdings underscore how the Winnes continually recognized the value of riverfront land for both transportation and trade. During the colonial period, rivers were the economic lifelines of the region, and securing ownership of key locations along them offered both strategic advantage and economic promise.

This grant further confirms the Winne family’s long-standing role in shaping the infrastructure of early New York. It also reflects broader trends in colonial land distribution, where rivers weren’t just barriers—they were arteries of prosperity, and the Winne family knew how to harness their potential.

Today, while the islands themselves may not be commonly known, their story remains a significant piece of New York’s early colonial puzzle—and Peter Winne’s 1741 grant stands as a lasting symbol of foresight, ambition, and the riverbound spirit that defined a generation of settlers.

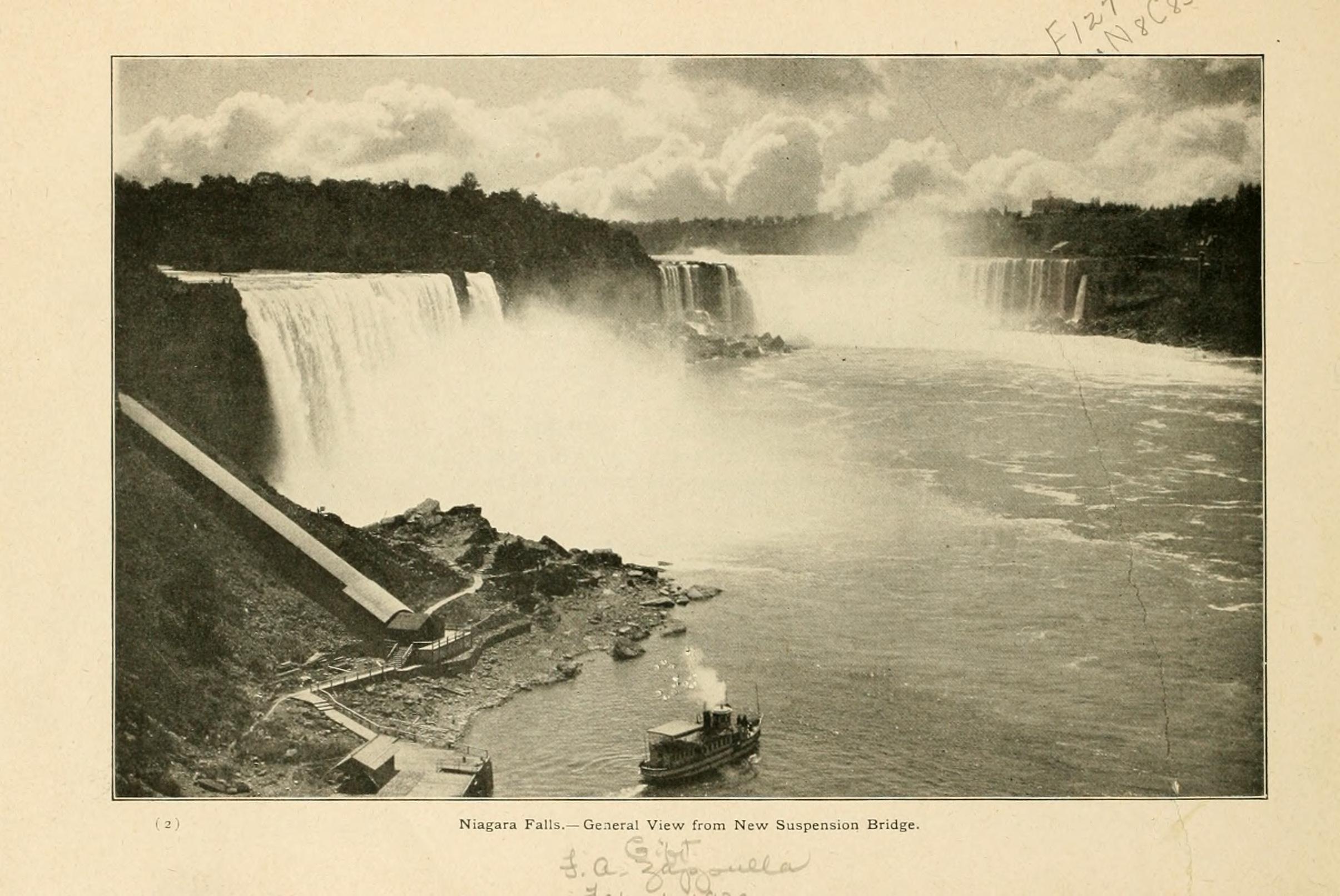

Barent Winne and Winne's Dock along the Hudson River

The Winne family has long been woven into the agricultural and commercial fabric of the Hudson Valley. Since their arrival from the Netherlands in 1652, the Winnes established themselves as innovative farmers and traders, utilizing the fertile lands along the Hudson and Mohawk Rivers to launch one of the earliest family-run agrarian enterprises in the region. Their story is deeply tied to the waterways that defined early American commerce and settlement.

As early as the 17th century, Pieter Winne—who settled near the Vlomankill in 1677—recognized the potential of the river valleys not just for farming, but for powering industry and connecting goods to distant markets. By the 1800s, Barent Winne Sr. carried this legacy forward, transforming the family’s agricultural strength into a thriving commercial operation. Situated at Cedar Hill, Winne’s Dock became a hub for regional trade, where Bethlehem farmers brought cash crops such as oats, hay, and apples. These goods were loaded onto barges bound for Albany and New York City, long before the convenience of railroads.

The dock wasn’t just a shipping point—it was the center of a bustling riverside economy. Barent Winne built large warehouses and a general store near his elegant brick home, where everything from coal and lumber to furniture and farm supplies passed through. Winne’s Dock even earned the nickname “Hudson River Landing,” serving not just as a freight depot but also a marketplace for farmers to purchase tools, food, and essentials. The creek nearby, the Vlomankill, helped power mills and facilitated even more industrial activity in the area.

As the community around Bethlehem grew, so did the importance of Winne’s Dock. Farmers and townspeople alike depended on it as their primary artery to the wider world, a critical link in the chain that connected remote farmland to urban markets. Even after the rise of railroads and the decline of river commerce, the legacy of Winne’s Dock lived on. Remnants of the wharf, iron fittings, and cement foundations are still visible near today’s Henry Hudson Park, echoing the past presence of commerce and innovation along the shoreline.

Barent Winne Jr., although childless, remained a steady presence at the homestead well into the late 19th century, known for watching the boats glide down the river from his front porch. His life—rooted in land, water, and community—symbolizes the enduring spirit of the Hudson Valley’s early farming families.

The Winne family’s expansion didn’t stop at Cedar Hill. Eventually, their agricultural endeavors spread into the Catskills, where they established farms along the Esopus River, continuing their tradition of cultivating rich lands and distributing goods using New York’s vast natural waterways. Their story is not just one of farming—it’s a narrative of foresight, resilience, and the foundational role of family-run operations in shaping regional commerce in early America.

Today, while only fragments of Winne’s Dock remain, the influence of the Winne family continues to ripple across the Hudson Valley, carried forward by those who still work the land and honor the legacy of those who first saw the river not as a barrier—but as a lifeline.

The Winne Family and Their Hudson River Legacy in the 1600s and 1700s

The Winne Family and Their Hudson River Legacy in the 1600s and 1700s

Origins of the Winne Family

The Hudson River: A Lifeline for Trade

Winne’s Dock: A Family Hub

Barent Winne and the Family Legacy

A Thriving Contribution

The Dutch Creation of New Netherland and Pieter Winne's Role

The Dutch Creation of New Netherland and Pieter Winne’s Role

Introduction

Historical Context: The Creation of New Netherland

Pieter Winne: Life and Arrival

Economic and Social Contributions

Role in the Colony’s Development

Legacy and Impact

Conclusion

|

Year

|

Event

|

|---|---|

|

1609

|

Henry Hudson explores the Hudson River, claiming the area for the Dutch.

|

|

1621

|

Dutch West India Company granted trade monopoly, leading to settlement plans.

|

|

1624

|

First permanent settlers arrive, establishing Noten Island settlement.

|

|

1625

|

Fort Amsterdam built on Manhattan, founding New Amsterdam.

|

|

1647

|

Peter Stuyvesant becomes director-general, overseeing colony growth.

|

|

1652

|

Pieter Winne arrives in New Netherland, settling near Fort Orange.

|

|

1664

|

English seize New Amsterdam, renaming it New York, ending Dutch control.

|