Denghoog and Wenningstedt on the Island of Sylt: A Glimpse into Neolithic History

Nestled on the windswept shores of the German island of Sylt in the North Sea, the village of Wenningstedt holds a remarkable piece of history: the Denghoog, a Neolithic burial mound that offers a window into the lives of the ancient North Frisian people. This blog post explores the significance of the Denghoog, its connection to the “Settlement of the Winne Clan,” and the broader historical and cultural context that ties this site to the migration of the North Frisian Winne family across centuries.

The Denghoog: A Neolithic Marvel

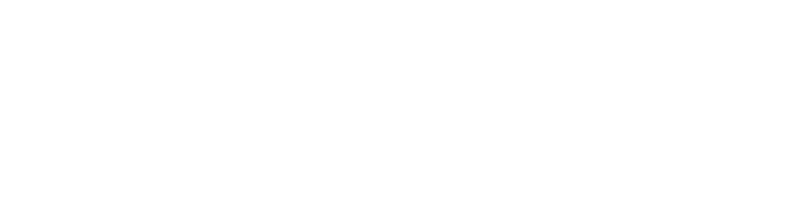

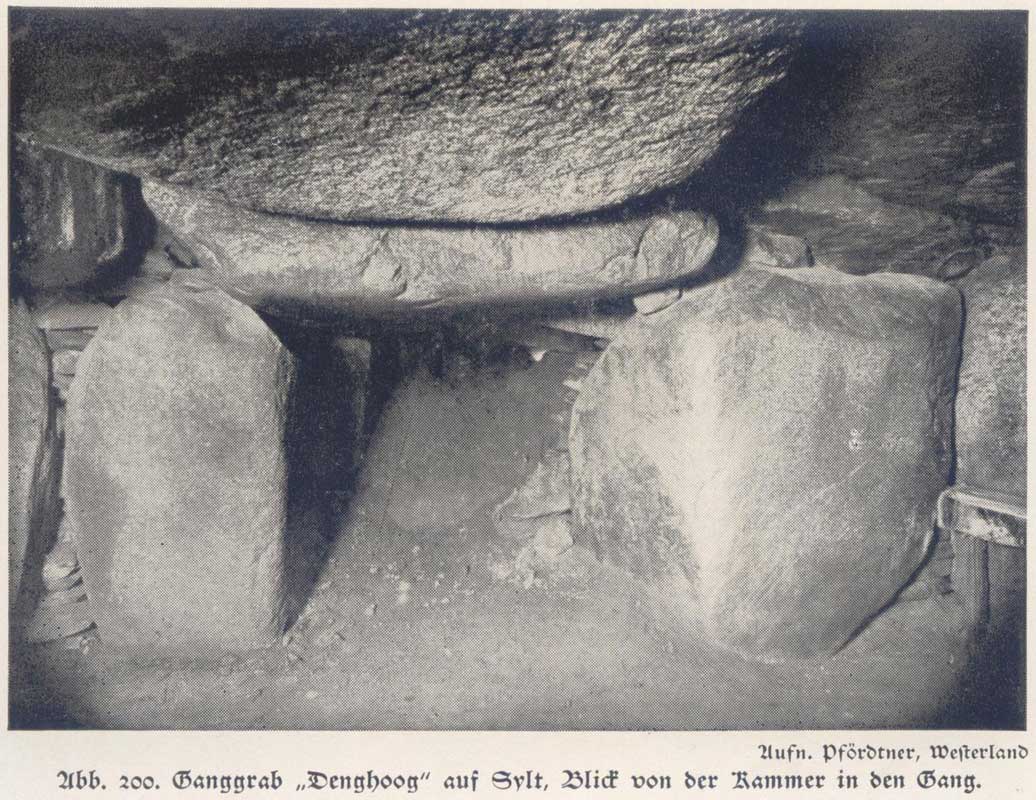

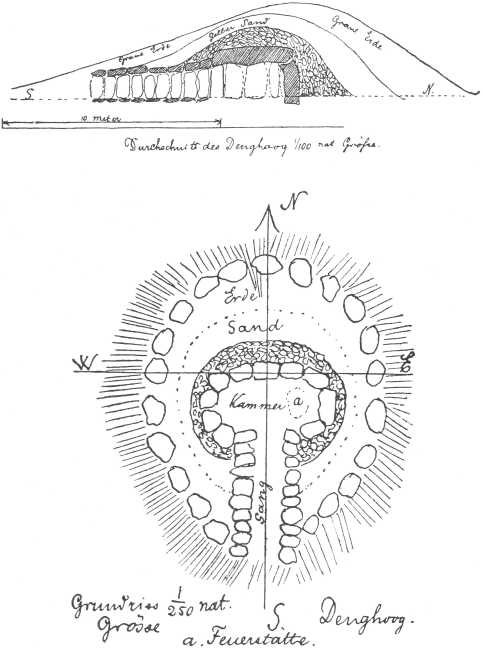

The Denghoog, located in Wenningstedt on Sylt, is a well-preserved megalithic tomb dating back to the Neolithic period (4100–1700 BC). Constructed by early farming communities, this passage grave consists of large stone slabs arranged to form a burial chamber, a testament to the engineering skills and spiritual beliefs of its builders. These structures, common across Northern Europe, were used for communal burials and likely held significant ritual importance, reflecting a society that honored its dead with care and reverence.

The name “Denghoog” itself, derived from the Frisian words deng (meaning “hill” or “mound”) and hoog (meaning “high”), describes the mound’s distinctive appearance on the flat landscape of Sylt. Excavations of similar sites suggest that the Denghoog may have contained grave goods such as pottery, tools, and ornaments, offering clues about the daily life, trade networks, and cultural practices of the Neolithic inhabitants.

Wenningstedt: The Settlement of the Winne Clan

According to the Chronik der Norddörfer auf Sylt, a historical chronicle published by the Nordfriisk Instituut in 1981, Wenningstedt was known as the “Siedlung der Sippe des Winne,” or the “Settlement of the Winne Clan.” This suggests that the area was a significant hub for a North Frisian family or clan known as the Winne. Given the proximity of the Denghoog to Wenningstedt, it’s reasonable to infer that this megalithic tomb may have served as a sacred or ancestral site for the Winne family, possibly their first “home” in a symbolic sense—a place where their forebears were laid to rest, anchoring their identity to the land.

The North Frisians, a distinct ethnic group with their own language and cultural traditions, have long inhabited the coastal regions of the North Sea, including Sylt. During the Neolithic period, these early inhabitants were likely part of the Funnelbeaker culture (named for their distinctive funnel-shaped pottery), which thrived in Northern Europe. The Denghoog, as a product of this culture, underscores the deep roots of the North Frisian people in this region.

The Journey of the Winne Clan

The story of the Winne Clan doesn’t end on Sylt. The Chronik der Norddörfer auf Sylt hints at a broader migration pattern, with the Winne family eventually moving southward through Germany and settling in Leeuwarden, Friesland, in the Netherlands. This migration reflects the dynamic history of the Frisian people, who navigated the challenges of changing climates, rising sea levels, and shifting political landscapes over millennia.

During the Neolithic period, Sylt was likely more connected to the mainland than it is today, as sea levels were lower. However, as the North Sea encroached, the Frisians adapted to their coastal environment, becoming skilled seafarers and traders. The Winne Clan’s journey from Sylt to Leeuwarden may have been driven by a combination of environmental pressures, economic opportunities, and cultural exchanges. By the time they reached Friesland in the Netherlands, the Frisians had developed a distinct identity, with their own language (West Frisian in the Netherlands, North Frisian in Germany) and traditions.

Leeuwarden, a historic city in the province of Friesland, became a cultural and economic center for the Frisians. The Winne Clan’s migration to this region likely contributed to the rich tapestry of Frisian heritage, which remains vibrant today through festivals, language preservation efforts, and historical research.

Connecting the Dots: Why the Denghoog Matters

The Denghoog is more than just a pile of stones; it’s a tangible link to the ancient past, connecting the modern-day visitor to the lives of the Neolithic North Frisians. For the Winne Clan, it may have served as a spiritual and cultural anchor, a place where their ancestors were honored and their communal identity was forged. The survival of the Denghoog through millennia of storms, wars, and modernization is a testament to its enduring significance.

For modern visitors to Sylt, the Denghoog offers a chance to step back in time. The site is accessible to the public, with a narrow passage allowing visitors to enter the burial chamber and experience the weight of history firsthand. Standing inside the Denghoog, surrounded by stones placed by hands over 5,000 years ago, one can’t help but feel a connection to the Winne Clan and their Neolithic world.

The Broader Context: North Frisian Culture and Legacy

The North Frisians, including the Winne Clan, were part of a resilient coastal culture that thrived despite the challenges of their environment. Their Neolithic ancestors built not only burial mounds like the Denghoog but also settlements, dikes, and boats, laying the groundwork for the maritime expertise that would define the Frisians for centuries. Today, the North Frisian language and traditions are preserved through institutions like the Nordfriisk Instituut, which continues to document and celebrate the region’s heritage.

The migration of the Winne Clan from Sylt to Leeuwarden also highlights the interconnectedness of Frisian communities across borders. While the North Frisians of Sylt and the West Frisians of the Netherlands developed distinct dialects and customs, they share a common ancestry rooted in the Neolithic landscapes of Northern Europe.