The New York Dutch Room, housed in Gallery 712 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, showcases the enduring influence of Netherlandish construction techniques in colonial New York.

Dutch settlers started arriving in the Hudson River Valley during the early 1600s, building homes and barns in a style reminiscent of their homeland. The primary room, known as a “groote kaner” in Dutch, originates from a 1751 house constructed for Daniel Pieter Winne (1720–1800). Winne’s ancestors had relocated from Flanders to Rensselaerswyck (modern-day Albany County) via Curacao in 1643.

Rather than being styled as a fully furnished historical space, the room is displayed as a gallery, highlighting furniture, metalwork, ceramics, and glassware typical of Dutch-descended households in the New York region.

Netherlandish Building Styles in Colonial America

Daniel Pieter Winne’s 1751 house, despite his family’s century-long presence in the Upper Hudson River Valley, retained a architectural style deeply rooted in medieval Dutch traditions.

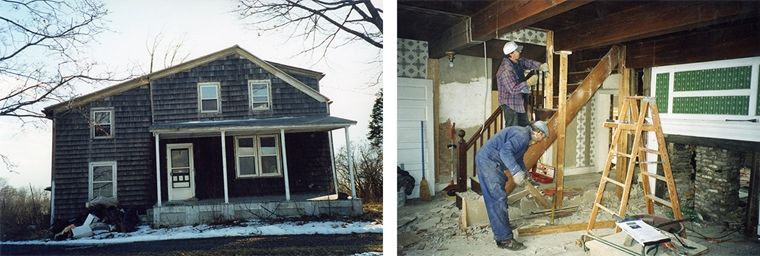

The Winne family occupied the house for generations. David Winne (1819–1882) and Catherine Winne (1827–1893) were the last to live there, though their daughter and granddaughter rented it out until it was sold in 1954.

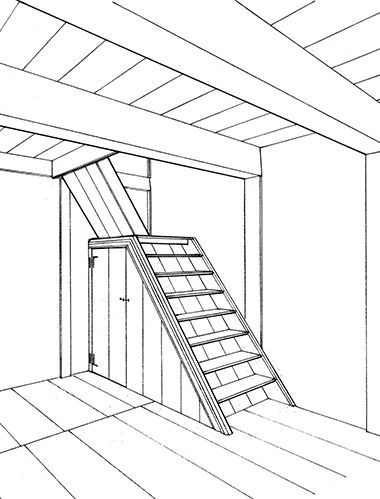

The Winne House consisted of two ground-floor rooms, a half-story attic, and a cellar. The larger of the two main rooms, now at The Met, originally featured a corner staircase near the front door, possibly with a built-in bed or cupboard in the opposite corner.

This central room served multiple purposes: cooking (evident from the large, open hearth), sleeping, socializing, and displaying prized possessions like ceramics, metalwork, textiles, and clothing.

When the Winne House was disassembled, fragments of Dutch tiles were found. These earthenware tiles, crafted in the Netherlands, were a staple in Dutch American homes during the 17th and 18th centuries. Typically arranged vertically between the floor and fireplace mantel, as seen in The Met’s display, they often depicted New Testament scenes and likely played a role in teaching children moral lessons in colonial New York.

The Winne House saw significant changes over the 19th century, masking its original design. In the early 1800s, the Winnes added rooms to the first floor and attic along the entry side, altering the roofline. Further expansions occurred in the 1850s or 1860s and again in the 1930s, with all doors and windows replaced multiple times.